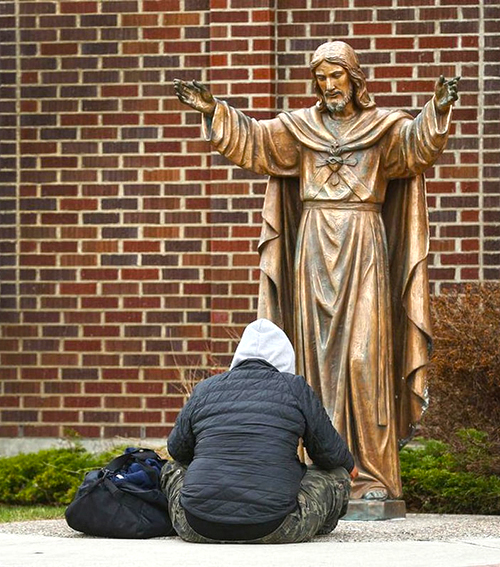

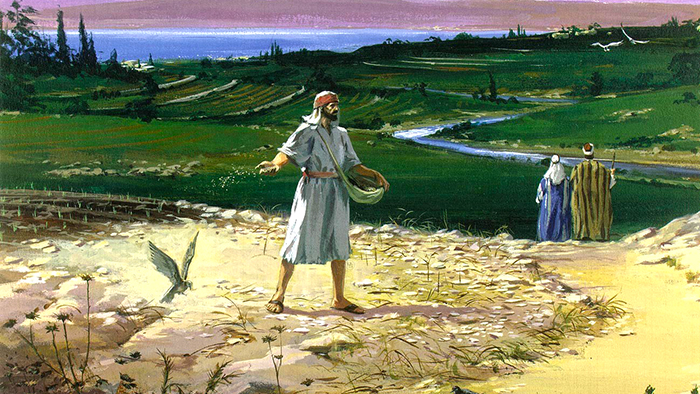

We, and everything on our planet, live because of the sun’s generosity. The sun reflects the abundance of God, a generosity that invites us also to be generous, to have big hearts, to risk more in giving ourselves away in self-sacrifice, and to witness God’s abundance. But Fr. Rolheiser writes this is challenging. Instinctually, we move more naturally toward self-preservation and security. By nature, we fear, and we horde. Because of this, whether we are poor or not, we tend to work out of a sense of scarcity, fearing always that we don’t have enough, that there isn’t enough, and that we need to be careful in what we give away, that we can’t afford to be too generous. But God belies this, as does nature. God is prodigal, abundant, generous, and wasteful beyond our small fears and imaginations. In the biblical parable of the Sower, the Sower scatters seeds indiscriminately everywhere: on the road, in the bushes, in the rocks, into barren soil, and good soil. It seems he has unlimited seeds, so he works from a generous sense of abundance rather than from a guarded sense of scarcity. God is equally as prodigal and generous in forgiveness, as we see in the gospels. In the parable of the Father, who forgives the prodigal son, we see a person who can forgive out of a richness that dwarfs dignity and calculated cost to self. From everything we can see, God is so rich in love and mercy that he can afford to be wasteful, over-generous, non-calculating, non-discriminating, incredibly risk-taking, and big-hearted beyond our imaginations. And that’s the invitation: to have a sense of God’s abundance and always risk a bigger heart and generosity beyond the instinctual fear. Jesus assures us that the measure we measure out is the measure that we ourselves will receive in return. Essentially, that says that the air we breathe out will be the air we re-inhale. If we breathe out miserliness, we will re-inhale miserliness; if we breathe out pettiness, we will breathe in pettiness; if we breathe out bitterness, then bitterness will be the air that surrounds us; and if we breathe out a sense of scarcity that makes us calculate and be fearful, then calculation and fearfulness will be the air we re-inhale. But, if we are aware of God’s abundance, we breathe out generosity and forgiveness; we will breathe in the air of generosity and forgiveness. We re-inhale what we exhale. To be generous and big-hearted, we must first trust in God’s abundance and generosity.