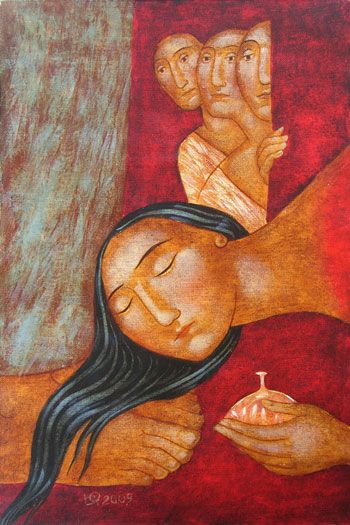

Nearly 2,000 years ago, two disillusioned youths consoled each other as they walked that seven-mile stretch of road separating Jerusalem from Emmaus. Fr. Rolheiser writes that they moved slowly, depression having taken the spring from their steps. A double feeling clung to their hearts that day. They were hurting, and there was reason. Their messiah and their dreams had just been crucified. A deep, dark disappointment dampened their spirits. And there was fear. Most of all, there was fear. Not fear that they themselves might be crucified. That prospect loomed more welcome than the thought of going on. Theirs was that more horrible fear, the fear that comes from the realization that perhaps nothing makes a difference after all; maybe our dreams and our hopes point to nothing more real than Santa and the Easter Bunny. The uncrucified Christ had filled them with a dream. With that dream had come a new innocence, freshness, energy, and a feeling absent since they had been children, which, prior to meeting Jesus, they had, long ago, unconsciously despaired of ever feeling again. Dreams are giving way before the caveat of the cynic; faith is daily being displaced by doubt; and perseverance and long-suffering are all but extinct in culture and church of release and enjoyment. Worst of all, there is fear, an unconscious fear whose tentacles are beginning to color every facet of life. It is the fear that perhaps our Christian hopes and dreams point to nothing beyond our own hopes and dreams. Perhaps faith is, after all, only a naiveté. Isn’t Christ as dead as he was on Good Friday? Who, save perhaps for a few good thieves, is still turning to a cross for salvation? Yet there is something else: The dream still clings to us, refusing to let us go. It burns holes in us still, hanging on to us, even when in infidelity and despair, we can no longer hang on to it. Hope is still more real than death. In our hurt, we are struggling for words and grasping for trust. We need to remain on the road to Emmaus. The stranger still stalks that same road. In his company, we need to discuss our doubts, discuss the scriptures, and continually offer each other bread and consolation. At some moment, our eyes will be opened, too. We will understand, and we will recognize the risen Lord. Then, the dream will explode anew like a flower bursting in bloom after a long winter. We will be full of a new innocence. Easter Sunday will happen again.